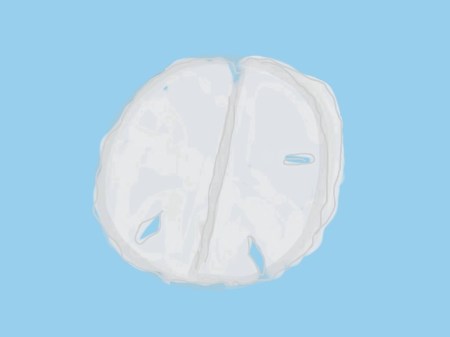

The above is my pictorial take on a photographic prompt of Tess Kincaid, of Magpie Tales, which, in turn, is a photograph of a sculpture by Jason deCaries Taylor. The picture looks a bit grim–my tale, below, is actually on the humorous side.

Pet Clam

When I was a young child, desperately wanting a pet to pat and love and call my own, I got a clam.

He or she (with mollusks, it’s hard to tell) sat on the crushed ice in the blue enamel shelf of the old A&P shellfish section. The lobsters who crawled around the murky bubbling tank in that area of the grocery store were clearly alive, but somehow I learned that the clams sprawled on the ice lived too, and one of them, stonily asserted itself, ‘pick me.’ With the permission of my mother, I brought him home and the next day took him into school for show and tell==(how the clam has suddenly become male, I’m not sure).

I don’t remember if he actually made it to show and tell. Only that at a certain point in my first grade afternoon, his jaw (as it were) drooped, the shell opening in my desk in the trough reserved for pencils, while dribble, like that that sometimes collects at the corners of the lips of the infirm, glimmered along the edges of his crack, his body a velvety mute tongue.

As an adult, I used to like to joke about the episode, until one morning when my own child was small, I pointed to a basket of clams sitting woodenly beside the counter of an old-fashioned Brooklyn fishmonger–we breathed through our mouths because of the reek–and told her that the clams were still alive–the merchant concurred–and how I myself had one owned one as a pet.

An awe=struck light filled her eyes.

I’m not sure what came over me. Typically, I try to be a good parent, shielding my children from heart-ache. Yet, in this instance, I invited it in–perhaps telling myself she needed experience of the world, perhaps tired of hearing requests for pets, perhaps because I thought she too would eventually join in upon the joke. I let her pick one. She chose carefully from the slats of the basket labeled Cherrystone.

In my defense, I did emphasize that clams were not in fact great pets, listing the obvious. She carried it proudly, gently from the store, in a paper bag which she peeked into often on the walk home, deciding upon the name of Cherry Merry Clam, a variation of her own name mixed with Cherrystone. (And Clam.)

Once home, she carefully alternated Cherry’s sojourns in the fridge, where it stared blindly up from the metal rack, with short visits to the couch, an old beigish velour, with a square back and arms that served as good ledges for the clam’s rounded bottom (and top).

Every few minutes of fridge time were punctuated by a request of whether Cherry could come out again. When she was released, my daughter stroked the clam’s ridged grey surface with a small forefinger, and spoke to it in those high-pitches reserved for coddled infants–babies, puppies, now clams. Occasionally, she would pass a finger over the line where the shell closed, telling me she thought it was smiling.

Guilt filled me. I replayed my own distress at the open clam languishing in my first grade desk. I warned my daughter of the clam’s vulnerability. Which, beyond serving as warning, raised the question of its care.

I realized that I knew nothing of clams. Did they drown/suffocate in the open air? Did they, inside that hard shell, suffer?

We rinsed Cherry in the sink. (Wait–what about the chlorine?) We put Cherry in a bowl of salted water.

As if glued to destiny, I let my daughter take Cherry to nursery school the next day where, despite best efforts and the school fridge, the clam opened, and the assistant teacher pronounced its passing.

It is difficult to mourn the death of a pet clam. There is a passivity about the creature that makes one’s grief seem ridiculous.

But grief is manifest in the mourner, not the bemoaned, and the loss of something imbued with love, whether or not it even smiled back, is grief-worthy.

So when I think of Cherry Merry now, I feel a true sadness–first, of course, for my daughter who genuinely suffered that day, then too, for myself–both as first grader, but more as guilty mother–the grief of any mother conscious of her mistakes and faced with their consequences.

And then, there’s a sadness simply at the death–not for the clam (no, not for the clam!) but for the struggle, or at least, the image of struggle–the seemingly gasping shell. (What does the clam do when it opens? What does it do when it shuts, for that matter?)

The visage of human death comes to mind–the fight for breath, the seeming drowning in air, the moment when this Earth (as one has known it) is no longer one’s element. Or maybe it’s the here and now that can no longer be processed at death–maybe that’s what can no longer be negotiated when our life escapes its shell in that unwilled opening.

P.S. Linking this to Imperfect Prose for Thursdays (Emily Weiranga’s meme.0

Recent Comments